Finland’s war preparations

The Finnish Army, i.e. the ground forces, played a key role in repelling the invasion by the Red Army. The enemy’s attack would focus on the Karelian Isthmus. In the area north of Lake Ladoga, the Red Army could only use division-sized formations up to the latitude of Suojärvi. They would not be attacked on the almost roadless wilderness front spanning from Suojärvi to the Arctic Ocean. During the war, the navy had to protect maritime routes and defend coastal areas. The air force’s main mission was to protect the troops and home region from air raids by the enemy. International agreements had established the Åland Islands as a demilitarised zone.

Finland aimed for wartime neutrality

After the dispute with Sweden over the Åland Islands had been settled by the League of Nations in Finland’s favour in 1921, Finland’s only potential remaining enemy was the Soviet Union.

The Finnish Defence Forces were developed throughout the interwar period to repel a potential attack by the Soviet Union. The premise in all assessments was that Finland would not be able to hold out for long alone in a war against the Soviet Union and would therefore require international assistance.

In addition to the possibility of an attack on Finland, the assessments also examined the eventuality of war in the Baltic Sea region. In this scenario, Finland’s aim would be to remain neutral. In the first phase, the first violations of Finland’s neutrality would take place on the coast of Southern Finland. The initial emphasis was solely on the credibility that was created by Finland’s military defence capability. Later on, attention was also paid to political credibility.

Finland prepared for an attack by the Soviet Union

Throughout the 1930s, Finland continued to develop its defence system to answer the growing military threat posed by the Soviet Union. The premise for this development was that the Soviet Union could attack Finland with superior ground, naval and air forces. However, the ground forces would be the main attacking force, assisted by the air force and, especially during the open water season, by the navy. The worst threat scenario was a surprise attack by the Red Army.

At the outset of the Winter War, Finland was almost finished preparing legislation for wartime conditions. This legislation was versatile, containing regulations concerning the citizens’ duties during a state of war, among other regulations. Compared to the Scandinavian countries, Finland had good military defence capabilities, although these were insufficient for fighting a great power alone.

The commander-in-chief of the Finnish Defence Forces started preparing for his duties in 1931

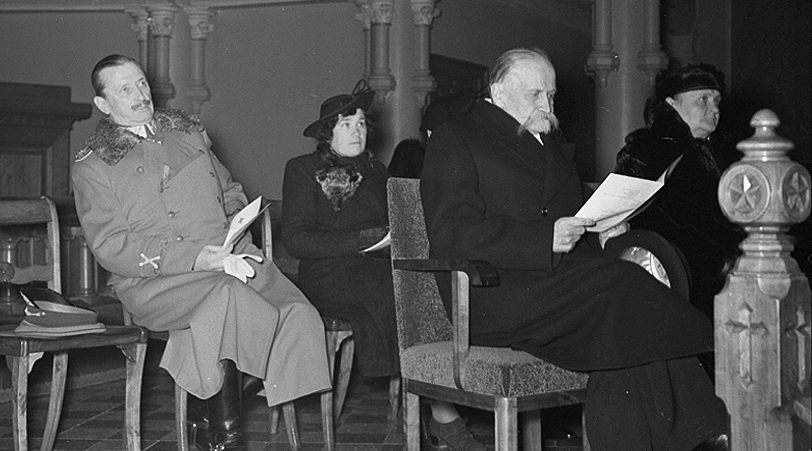

President Kyösti Kallio and the future commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Gustaf Mannerheim, at a church concert of the Finnish Red Cross on 1 November 1939. SA-kuva.

President Kyösti Kallio and the future commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Gustaf Mannerheim, at a church concert of the Finnish Red Cross on 1 November 1939. SA-kuva.

One of the peculiarities of Finland’s defence preparations was that Gustaf Mannerheim, who was a general of the cavalry at the time, was already appointed chairman of Finland’s Defence Council in 1931. The Defence Council was tasked with determining the direction for the development of the wartime Defence Forces. The appointment of Mannerheim by President Pehr Evind Svinhufvud (1931−37) initially involved the undisclosed idea that the role of the commander-in-chief, which was held by the president, would be assigned to Mannerheim at the outbreak of war. President Kyösti Kallio (1937−40) approved his predecessor’s decision. The future commander-in-chief therefore had eight years to prepare for his demanding role.

Assistance from the West was considered to be vital in a war with the Soviet Union

The Finnish General Staff primarily saw a potential war against the Soviet Union as part of a wider European war. The military command considered the aim of defensive combat to be long-term resistance that would establish the conditions for other states to participate in defending Finland.

Political efforts to obtain international assistance in the event of an outbreak of war were still far from complete at the outbreak of the Winter War. In December 1935, the government of Prime Minister T. M. Kivimäki issued a formal statement to the parliament, announcing that Finland was in favour of the neutrality of the Nordic countries.

Finland refused to participate in sanctions imposed by Article 16 of the League of Nations

Out of the small, neutral countries in Europe, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg had signed an agreement in Oslo in 1930 that primarily pertained to customs and trade relations. The goal of these countries was to safeguard their neutrality during a possible war. Finland joined these countries, which were known as the Oslo states, in 1933. In summer 1936, the Oslo states declared that they would not automatically participate in imposing the sanctions set out in Article 16 of the League of Nations against an aggressor. The countries would consider following the regulation separately in each case. Furthermore, they declared that they would refuse to follow the Covenant’s stipulation that foreign forces be allowed passage through their territory against an aggressor.

The attempts to commit Sweden to Finland’s defence failed

Mannerheim considered Finland’s declaration of its pro-Nordic policy to be a kick-start to Finland’s efforts to make an agreement with Sweden regarding mutual wartime assistance. Finland first tried to make this agreement through the League of Nations. However, Sweden declared in the League of Nations in 1936 that it would not sign any agreements that would exceed the obligations set out in the Covenant.

As the situation in Europe became more fraught, however, Sweden was prepared to start negotiations with Finland on the mutual defence of the Åland Islands. The two governments signed an agreement in 1938. However, after the outbreak of the Winter War, the Swedish government decided not to make a proposal to the Finnish Parliament regarding the application of the agreement.

Ari Raunio

SUOMEKSI

SUOMEKSI PÅ SVENSKA

PÅ SVENSKA по-русски

по-русски